INTRODUCTION

Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome is a rare but potentially vision-threatening complication of intraocular surgery, characterized by the triad of anterior uveitis, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and hyphema. First described by Ellingson in 1978 in association with early anterior chamber intraocular lenses (IOLs), the syndrome has since been reported with various IOL types and surgical approaches, including posterior chamber lenses and minimally invasive glaucoma surgery [1, 2].

Although modern lens design and surgical techniques have reduced the incidence of UGH syndrome – from 2.2-3% in earlier reports to approximately 0.4-1.2% in recent series – it remains a relevant clinical entity [3]. Mechanical irritation between an IOL and the iris or ciliary body can lead to pigment dispersion, iris transillumination defects, anterior uveitis, microhyphema or frank hyphema, vitreous hemorrhage, and cystoid macular edema (CME). Elevated IOP may occur acutely or with recurrent episodes, resulting in progressive optic nerve damage.

The pathophysiology of glaucoma in UGH syndrome is multifactorial. It includes obstruction of the trabecular mesh-work by inflammatory debris, erythrocytes, ghost cells, and fibrin, along with the formation of peripheral anterior synechiae [4]. Although the condition typically develops months or years after surgery, early-onset cases have also been reported.

Diagnosis can be challenging due to the overlap with other causes of anterior uveitis and secondary glaucoma. Slit-lamp biomicroscopy and gonioscopy remain essential tools, while imaging modalities – particularly ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) – are crucial for confirming mechanical chafing between the IOL and surrounding structures.

Treatment depends on the severity and persistence of inflammation and IOP elevation. While initial management may involve anti-inflammatory and hypotensive agents, surgical intervention is often necessary in refractory cases. This includes IOL repositioning or explantation to eliminate the source of mechanical irritation.

We report a diagnostically complex case of UGH plus syndrome, in which delayed recognition led to multiple surgical interventions before definitive resolution was achieved following IOL explantation.

CASE REPORT

A 42-year-old woman presented with recurrent pain and visual loss in her left eye. She had a history of bilateral juvenile cataract extraction with posterior chamber intraocular lens (PCIOL) implantation in 2015. Since 2022, she had experienced recurrent anterior uveitis of unknown etiology in the left eye, alongside an episode of vitreous hemorrhage in August 2024. Workup for auto- immune and inflammatory diseases, including HLA-B27, ANA, and ANCA, was negative. Her general medical history was un-remarkable.

On initial presentation, best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 0.9 in the right eye and 0.5 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed dispersed blood in the anterior chamber, small nongranulomatous keratic precipitates on the corneal endothelium, iridodonesis, and an eccentrically positioned pupil. Marked iris transillumination defects were noted in the left eye. Intraocular pressure (IOP) was elevated (~60 mmHg) despite maximal medical therapy, including topical latanoprost, timolol, dorzolamide, brimonidine, and oral acetazolamide (250 mg twice daily). Fundus details could not be visualized due to media opacity, but B scan ultrasound showed dense, mobile vitreous opacities suggestive of hemorrhage or inflammation.

The patient underwent urgent trabeculectomy in September 2024, along with intensive anti-inflammatory therapy (topical dexamethasone and oral methylprednisolone). The early postoperative course was complicated by hypotony and choroidal detachment, managed with two intracameral viscoelastic injections. In October, she developed recurrent hemorrhage in both the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity, with IOP spikes.

Subsequent interventions included YAG laser suture lysis and needling revision, both of which failed to achieve lasting IOP control. Recurrent inflammation, vitreous hemorrhage, and anterior chamber bleeding occurred in the following 2 months. Her visual acuity deteriorated to hand motion in the affected eye.

Short-term IOP stabilization was achieved with topical atro-pine, which had to be discontinued due to intolerance. A revision trabeculectomy in December 2024 failed to control IOP. Pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with preoperative intravitreal bevacizumab was performed in January 2025 due to persistent vitreous hemorrhage, but no active bleeding site was found intraoperatively. Visual acuity temporarily improved postoperatively, but hemorrhages recurred within two weeks.

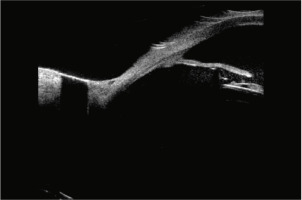

Ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) revealed peripheral iridocorneal touch and mechanical iris–IOL chafing, confirming the diagnosis of UGH plus syndrome. The patient underwent surgical explantation of the PCIOL in January 2025.

At 6-week follow-up, her IOP remained stable (14-16 mmHg), and there was no recurrence of hemorrhage or inflammation. The patient remains under regular follow-up care.

Written informed consent for publication of this case and all related images was obtained from the patient.

Summary of therapeutic interventions in a patient with UGH plus syndrome is shown in Table I.

Table I

Summary of therapeutic interventions in a patient with UGH plus syndrome. Chronological progression of clinical signs, treatments, and outcomes

[i] AC – anterior chamber; BCVA – best-corrected visual acuity; CME – cystoid macular edema; IOL – intraocular lens; IOP – intraocular pressure; OD – right eye; OS – left eye; PCIOL – posterior chamber intraocular lens; PPV – pars plana vitrectomy; UBM – ultrasound biomicroscopy; UGH – uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema; VA – visual acuity; VC – vitreous cavity

RESULTS

Following IOL explantation in January 2025, the patient demonstrated immediate clinical improvement. Intraocular pressure stabilized within the range of 14-16 mmHg without the need for additional hypotensive agents. Anterior segment examination showed a clear anterior chamber with no evidence of recurrent inflammation, microhyphema, or hyphema. No pigment dispersion or keratic precipitates were observed. The previously noted iris transillumination defects remained visible, but no new signs of iris chafing were detected.

Fundus visualization was possible due to the resolution of media opacity, with no evidence of persistent vitreous hemorrhage or cystoid macular edema. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed a normal macular profile. The patient’s best-corrected visual acuity in the affected eye improved to 0.6 within 6 weeks postoperatively.

At the last follow-up, the patient remained clinically stable, without recurrence of intraocular inflammation, hemorrhage, or IOP elevation. No additional surgical interventions were required. The patient declined secondary IOL implantation and remained aphakic, using aphakic correction as needed.

DISCUSSION

Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome represents a rare yet serious complication of intraocular lens (IOL) implantation, resulting from chronic mechanical irritation between the IOL and adjacent uveal tissues. Classically, it is characterized by anterior uveitis, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), and hyphema.

However, variants such as incomplete UGH (presenting with only one or two signs) and UGH plus syndrome (including vitreous hemorrhage) have also been described [5-9].

In the presented case, the diagnosis of UGH plus syndrome was delayed due to overlapping features with secondary inflammatory glaucoma. The presence of recurrent vitreous and anterior chamber hemorrhage, in combination with uncontrolled IOP despite surgical intervention, should have raised early suspicion of a mechanical etiology. Despite multiple interventions – including trabeculectomy, revision surgery, and vitrectomy – definitive improvement was only achieved following IOL explantation.

Slit-lamp examination remains essential in identifying key signs such as pigment dispersion, iris transillumination defects, and eccentric pupils. However, ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) is often required to detect subtle iris-IOL contact or haptic mispositioning that may not be visible clinically [10]. In our case, UBM confirmed peripheral iris-IOL chafing, leading to a final diagnosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Ultrasonic biomicroscopy (UBM). IOL of a foldable piece making contact with the posterior face of the iris

Management of UGH syndrome involves treating both the inflammatory component and the IOP elevation. Topical corticosteroids are typically the first-line treatment for intraocular inflammation, while IOP-lowering agents such as β-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and α-agonists are used concurrently. Prostaglandin analogues may exacerbate inflammation and should be used cautiously in uveitic eyes [11-13]. In refractory cases, surgical approaches including trabeculectomy, PPV, or ultimately IOL explantation may be required.

In this patient, the definitive resolution of symptoms following IOL removal confirms the diagnosis of UGH plus syndrome. The recurrence of bleeding and inflammation after multiple procedures, including anti-VEGF injection and vitrectomy, highlights the importance of early imaging and consideration of mechanical causes. Although secondary IOL implantation is an option, the patient declined further surgical management.

This case underscores the diagnostic difficulty of atypical UGH syndrome and the critical role of UBM in identifying mechanical causes of intraocular inflammation and hemorrhage. Earlier recognition of iris-IOL conflict could prevent unnecessary interventions and irreversible vision loss.

CONCLUSIONS

The diagnosis of UGH syndrome can pose an important diagnostic problem due to its rarity and variety of clinical presentations. It generally consists of the classic triad of complications: uveitis, glaucoma and hyphema, considered complete UGH syndrome. However, there are descriptions in the literature of so-called incomplete UGH syndrome: Sousa et al. [5], Zhang et al. [6], Foroozan et al. [7], Rhéaume et al. [8]; or the UGH syndrome plus, which additionally includes vitreous hemorrhage [9]. The common feature is always contact between the iris or ciliary body and the IOL. The malpositioned IOL causes iris trauma, which triggers an inflammatory cascade, pigment release and bleeding, leading to IOP elevation and glaucoma.

As in the above-described case, bleeding into the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity in the presence of an unstable iris diaphragm and IOL implant should raise suspicion for UGH syndrome. A thorough slit lamp examination is crucial to confirm the diagnosis. Some associated signs include pigment on the endothelium or in the anterior chamber, asymmetric pigment in the angle, iris transillumination defects, uveitis, vitreous hemorrhage, posterior vitreous detachment, and retinal tears or detachment [10]. Ultrasound biomicroscopy can also assist in the diagnosis of UGH syndrome by detecting iris-implant contact and haptic position [10].

According to the literature, UGH syndrome can be managed medically with conservative therapy or surgically. To address inflammation, topical and systemic corticosteroids can be used, especially in the case of CME development [11]. Elevated IOP is generally first treated with topical medication, such as β-adrenergic antagonists, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, α-adrenergic agonists, and eventually prostaglandins [12], although some authors suggest avoiding prostaglandins in the setting of uveitis [13, 20]. In the case of refractory high IOP, proceeding to glaucoma surgery such as trabeculectomy is a valid option. The definitive treatment often requires IOL repositioning or exchange, depending on the clinical picture. Careful attention should be paid to the position, ensuring that it is away from the iris and ciliary processes to avoid UGH syndrome relapse [14].

In our case, conservative treatment failed, and implant removal eventually prevented recurrent bleeding into the anterior chamber and vitreous cavity, stabilizing IOP. Secondary implantation is considered a future option, though currently postponed due to the patient’s reluctance [15].

Uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema syndrome can be devastating both for the patient and the clinician. Therefore, timely diagnosis is important to avoid unnecessary interventions and complications. Awareness should be raised to facilitate diagnosis, especially given the continuous evolution of intraocular surgical techniques.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH