INTRODUCTION

Uveal melanoma (UM) is the most common primary intraocular tumor in adults [1]. While melanoma can develop in any part of the uvea, the majority of UMs are found in the choroid. There is an ongoing debate about whether choroidal melanomas (CM) originate de novo in the choroid or develop from preexisting choroidal nevi (Figure 1) [2]. Despite recent advancements in ocular treatments that have allowed the preservation of the eye with functional vision in most cases, the overall survival rate of UM patients has not significantly improved over the past decades. The exact timing of metastatic cell development remains unknown, though it has been demonstrated that lethal mutations in tumor tissue can occur very early in the disease process [3]. Therefore, early tumor diagnosis and prompt intervention, especially in cases involving malignant transformation of preexisting nevi, are crucial and may impact patient survival [4, 5].

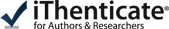

Figure 1

Nevus with a documented growth into a melanoma in a 72-year-old patient within 9 months. The lesion was observed for more than 10 years and no features of progression were detected: A) color fundus photography of the observed nevus; B) fundus autofluorescence. photography showing mildly hyperautofluorescent drusen (arrow); C) ultrasound image showing mildly hypoechogenic lesion (red asterisk); D) color fundus photography after 9 months with evident growth; E) fundus autofluorescence photography of the newly appeared orange pigment in the upper portion of the lesion (double arrow); F) ultrasound image of growing hypoechogenic lesion (red asterisk)

Choroidal melanocytic lesions are commonly detected during routine fundus examinations, with most being benign choroidal nevi (CN), the most frequent intraocular tumor in adults. Studies indicate that the prevalence of CN in the general population ranges from 0.3% to 6.5% and does not significantly differ between males and females [6-11]. The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) found the highest CN prevalence among Caucasians compared to Blacks, Hispanics, and other ethnic groups [7, 11]. Additionally, the NHANES study reported higher CN prevalence in overweight and obese postmenopausal women and in women whose last childbirth occurred before age 25, suggesting a potential influence of estrogens on CN development [11].

Choroidal melanoma, while the most common primary intraocular malignancy, remains a rare condition. According to the European Cancer Registry (EUROCARE), the incidence rate of CM ranges from 1.3 to 8.6 cases per million per year, with prevalence increasing with geographical latitude, peaking among Scandinavians and being lowest in sub-Mediterranean populations [12]. CM is extremely rare in children, with incidence increasing with age and peaking around 70 years [12-14]. However, recent trends show a lower age at diagnosis across different populations, which may reflect improved disease understanding and advancements in diagnostic techniques [15-17].

All melanocytic lesions require careful evaluation through clinical assessment and various imaging modalities, including color fundus photography, fundus autofluorescence photography, optical coherence tomography, and ultrasound. Vascularity assessment methods, such as fluorescein and indocya-nine green angiography (AF and ICGA) or OCT angiography (OCTA), can also be utilized in the diagnostic process.

FROM NEVUS TO MELANOMA

Historically, any “dark spots” observed inside the eye were presumed malignant, often leading to enucleation of the affected globe. However, extensive histopathological research conducted on enucleated eyes by Lorenz, Zimmermann, and colleagues at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Eye Pathology Section, established the theory that CN can undergo malignant transformation into CM [18, 19]. Unfortunately, it became evident that conservative treatments for CM, such as brachytherapy, did not significantly impact overall survival due to metastatic spread. Findings from the Collaborative Melanoma Study (COMS) confirmed that the mortality rate remained unchanged regardless of the primary tumor treatment method, with up to 50% of patients dying within 10 years of diagnosis [20, 21].

Recent studies, however, suggest that early intervention may positively influence patient survival [22]. A separate multicenter study found that distant metastasis is unlikely unless the lesion exceeds 3 mm in the largest basal diameter [23].

IMAGING OF DIFFERENT CHOROIDAL MELANOCYTIC TUMORS

A comprehensive assessment of melanocytic lesions requires the use of various imaging modalities. Each lesion should be routinely evaluated using optical coherence tomography (OCT), color fundus photography, fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and ultrasound (US) measurements [24, 25]. Fluorescein angiography (FA) and indocyanine green (ICGA) angiography can be valuable tools in the differential diagnosis of ambiguous cases, such as detecting choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in CN with subretinal fluid, or identifying pinpoint leakage (FA) and/or double circulation (ICGA) in nevi undergoing malignant transformation or in small CMs [26, 27]. Additionally, OCT angiography can aid in diagnosing CNV and evaluating the internal vascularity of melanocytic lesions. Table I presents the distinctive imaging characteristics of typical choroidal nevi, atypical CN, and CM.

Table I

Comparison of choroidal melanocytic lesion findings according to different imaging modalities

CLINICAL TOOLS FOR DIFFERENTIATION OF MELANOCYTIC LESIONS

Although molecular studies provide an insight into CM behavior, it is still mainly confined to scientific research. Everyday clinicians, when diagnosing choroidal melanocytic lesions need on-hand tools to make therapeutic decisions immediately, since the delay in recognizing malignancy may influence patient’s survival. This need was a driver for the search for clinical features that could aid in distinguishing benign CN from CM without the need for invasive procedures and therefore could guide earlier treatment implementation.

TFSOM

The first big analysis on prognostic clinical findings was presented by Shields et al. in 1995 [28]. A group of 1,329 patients with small (< 3 mm) choroidal melanocytic tumors were studied for symptoms correlating with tumor growth and risk for metastatic disease. The features related to tumor growth were tumor thickness > 2 mm, presence of subretinal fluid (SRF), flashes and floaters (symptoms), presence of lipofuscin deposits on the tumor’s surface (orange pigment), and posterior tumor margin within 3 mm from the optic disc. The factors predictive of metastatic disease were greater thickness of the lesion, posterior tumor margin at the optic disc, and documented growth. It is worth noting that a low growth rate (up to 0.5 mm) may be observed during the natural course of benign nevi [29], but many benign lesions remain stable over time (Figure 2). The presence of 3 risk factors was related to over 50% risk of tumor growth, and the combination that was most dangerous, with growth risk of 69%, was thickness > 2 mm, location at the disc margin, and symptoms. The authors developed a mnemotechnic to easily remember those five features – ‘‘To Find Small Ocular Melanoma’’ (thickness > 2 mm, subretinal Fluid, Symptoms, Orange pigment, location at the disk Margin) – which quickly proved very useful in everyday clinical practice [28, 29] and remained so for years.

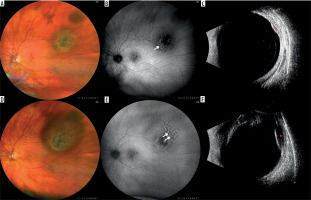

Figure 2

Small melanocytic lesion in a 68-year-old patient with no documented growth over a period of 4 years: A) color photography of the lesion at the first visit; B) autofluorescent photography of the lesion at the first visit; C) optical coherence tomography scan through the lesion at the first visit; D-F) corresponding images of the same lesion at the last follow-up

TFSOM-UHHD

In 2009, the same group of clinicians from Wills Eye Institute updated the list of prognostic factors, including previously absent ultrasonographic (US) findings [29]. Those new features included ultrasound hollowness of the elevated lesion and absence of halo on a fundus examination as two new factors for CN transformation. In addition, research results from the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study, where lack of drusen over the melanocytic lesion was also related to transformation [30], were also included in the updated version of the risk factors list. Therefore, the mnemotechnic was extended to TFSOM- UHHD – ‘‘To Find Small Ocular Melanoma Using Helpful Hints Daily’’ – where the additional letters stood for Ultrasound Hollowness and the absence of Halo and Drusen [29].

TFSOM-DIM

However, in 2019, a decade later, in view of the recent developments in imaging techniques Shields et al. presented a retrospective analysis on a group of 2,355 choroidal melanocytic lesions with long follow-up using more accurate imaging data. As a result, it established the importance of multimodal imaging in the identification of risk factors for CN transformation into CM. Shields et al. presented the most up-to date list of risk factors, which are (in order from the highest transformation hazard ratio): lesion thickness > 2 mm, presence of SRF (as a cap over the lesion or up to 3 mm from the lesion margin), presence of orange pigment, symptomatic vision loss ≤ 0.4 on Snellen visual acuity, acoustic hollowness in US and, finally, lesion diameter > 5 mm on color fundus photography. This list resulted in creating the currently used mnemotechnic – “To Find Small Ocular Melanoma Doing Imaging” (TFSOM-DiM) – with a change in “M” that now represents Melanoma ultrasound hollowness, and “DiM” representing DiaMeter > 5 mm (Figure 3). A summary is presented in Table II. Shields et al. also presented the estimated 5-year transformation hazard for those risk factors, being 1% for lesions without any risk factor, 11% with 1 factor, 22% with 2 factors, 34% with 3 factors, 51% with 4 factors, 55% with 5 risk factors, and inestimable with all visible risk factors [24, 31]. In other analysis, they also proved the proportional relation of tumor thickness with the transformation risk rate [32].

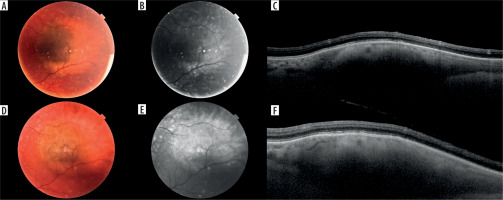

Figure 3

Giant nevi in 58-year-old patient, located close to the optic disc with drusen and no other risk factors for malignant transformation (T-F-S-O-M-DiM+): A) color fundus picture; B) fundus autofluorescence photography showing mildly hyperautofluorescent drusen (arrow); C) optical coherence tomography showing hyperreflective choroidal nevus (white arrows) with drusen (blue arrow) and its location close to the optic nerve

Table II

TFSOM-DiM (according to Shields [24])

| To Find Small Ocular Melanoma Doing Imaging | |

|---|---|

| T | Thickness 2 mm on US |

| F | Subretinal Fluid on OCT |

| S | Symptoms – visual acuity 0.5 |

| O | Orange pigment on FAF |

| M | Melanoma hollowness in US |

| DiM | Diameter 5 mm |

MOLES

In 2022, driven by the rapid changes in healthcare models after COVID-19 and economic motives, Damato et al. presented a new scoring system for probability of recognition of a malignant choroidal lesion based on fundus imaging and OCT only. The primary reason for this was to present a simple and accessible tool for optometrists and ophthalmologists to simplify the referral pathway to the tertiary-referral ocular oncology centers. The authors point out that the system does not need ultrasound, making it easier to apply even without expensive diagnostic devices. In this grading system, 5 features of the lesion are scored: mushroom shape, orange pigment, large size, enlargement, and presence of SRF (Figure 4). Their first letters form an acronym – MOLES. Every diagnostic feature undergoes further scoring from 0 to 2 depending on presence or absence of typical findings [33-35]. The MOLES scoring is presented in Table III.

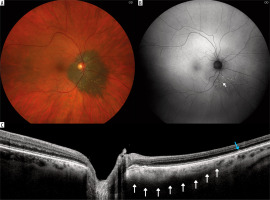

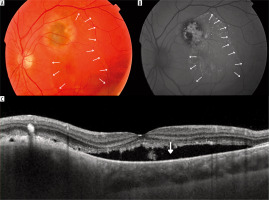

Figure 4

Melanocytic lesion found in 14-year-old patient, images at first visit: A) color fundus photography showing slightly elevated lesion accompanied by visible subretinal fluid (its margin lined with arrows); B) autofluorescence photography revealing presence of orange pigment and subretinal fluid (margin lined with arrows); C) OCT image of the lesion with accompanying subretinal fluid (arrow); MOLES score 4 (M-0, O-2, L-0, E-0, S-2) – urgent referral to ocular oncologist is recommended

Table III

MOLES criteria (according to Damato [35])

According to the final score, the lesions can be divided into four groups – “common naevus”, “low-risk naevus”, “high-risk naevus” and “probable melanoma” (Table IV), reducing unnecessary referral to ocular oncology centers but speeding it up to the last group of patients with probable malignancy [34]. In a recent study by Ching et al., the authors suggested ignoring the tumor thickness as it influenced the MOLES score in only 8.6% of cases, with the tumor diameter being more important for the final result (91.4% of cases) [36]. This is an interesting finding, given that tumor thickness is one of the key transformation risk factors in Shields’ TFSOM-DiM. However, Damato et al. emphasize the complementarity of the MOLES and TFSOM-DiM systems, the former being designed for non-experts to guide the referral process, and the latter for experts estimating the likelihood of malignant transformation [35].

Table IV

MOLES groups according to obtained score and suggested management (according to Damato [35])

TUMOR BIOPSY AND GENETIC TUMOR ANALYSIS

Thorough investigations into the genetics of CM have deepened our understanding of the specific mutations involved in CM oncogenesis and its metastatic processes. Crucial mutations in driver genes, notably GNAQ, GNA11, BAP1, EIF1AX, and SF3B1, play a pivotal role in the development of CM [37, 38]. Molecular analyses have enabled the classification of CM into two distinct groups – class 1 and class 2. The detection of driver gene mutations, along with chromosome 3 (Ch3) monosomy (M3) or disomy (D3), acts as an indicator of the meta-static risk associated with the primary tumor [38, 39].

Chromosome 3 monosomy (M3)

Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) is the predominant chromosomal abnormality in CM, occurring in approximately half of all tumors [40]. This anomaly involves a locus for the BAP1 driver gene, and its presence is an unfavorable prognostic factor for future metastatic disease [40-43]. LOH is predominantly associated with CM, with infrequent occur-rence in other types of tumors. It often coexists with additional chromosomal mutations, notably the gain of 8q11.21– q24.3, 6p25.1–p21.2, 21q21.2–q21.3, and 21q22.13–q22.3, and the loss of 1p36.33–p34.3, 1p31.1–p21.2, 6q16.2–q25.3, and 8p23.3–p11.23 [30]. Furthermore, tumors carrying this genetic defect are frequently larger, more commonly located in the ciliary body, and exhibit epithelioid cells and closed vascular patterns [43]. Another mutation affecting chromo-some 3 (Ch3) with similar clinical implications is isodisomy 3, also referred to as functional monosomy [44].

Chromosome 3 disomy (D3)

Its presence is closely associated with a more positive outlook and enhanced overall survival [45], given that Ch3 hosts the BAP1 gene locus [41, 42]. Notably, tumors with D3 more frequently exhibit simultaneous mutations in SF3B1 compared to those with M3 (29% vs. 3%). This co-occurrence implies a slightly heightened risk of metastases compared to most class 1 tumors [46].

GNAQ and GNA11

GNAQ and GNA11 are located on chromosomes 9q21.2 and 19p13.3, respectively. The genes share a coding region with more than 90% sequence homology, consisting of 7 exons [47]. Mutations in these genes, identified in 80-90% of CM, play a pivotal role in activating the RAF/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MEK)/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway. This activation leads to overexpression of the cell-cycle regulatory protein cyclin D1 (CCND1) and the inactivation of the tumor suppressor RB1 (RB transcriptional corepressor 1), ultimately resulting in cell proliferation [48, 49]. Vader et al. observed the presence of GNAQ/11 mutant clones in a fraction of common nevus (CN) cells, confirming that this mutation is not exclusive to CM and emerges early in oncogenesis [50, 51].

BAP1

As previously mentioned, this gene is located on chromo-some 3 (3p21.1) and functions as a tumor suppressor. It encodes nuclear ubiquitin carboxyterminal hydrolase (UCH), participating in deubiquitinating pathways that regulate DNA damage repair, cell division, apoptosis, and immune response [41, 51–53]. Loss of BAP1 occurs early in the development of CM and is likely associated with the formation of micrometastases [54]. Additionally, BAP1 has been linked not only to CM but also to other malignancies such as malignant mesothelioma, renal cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and cutaneous melanoma [41]. While most patients with BAP1 alterations have somatic mutations, a small group of CM patients exhibit BAP1 tumor predisposition syndrome, where a germline mutation of BAP1 is associated not only with specific skin lesions such as basal cell carcinoma and BAP1-inactivated melanocytic tumors but also with more aggressive class 2 CM, malignant mesothelioma, skin melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma [42, 52].

SF3B1

Found on chromosome 2 (2q33), this gene plays a critical role in pre-mRNA splicing and acts as one of the contributors to DNA damage repair [55–57]. A specific mutation occurring in codon 625 of the SF3B1 gene is unique to CM and is present in 14-20% of cases [58–60]. In CM categorized as the less aggressive class 1, the presence of an SF3B1 mutation is frequently associated with the expression of the PRAME oncogene. PRAME functions as an independent prognostic biomarker in CM, indicating a heightened metastatic risk. Consequently, some authors propose that these molecular findings imply the existence of an intermediate metastatic risk group, serving as a bridge between class 1 and class 2 tumors [60, 61].

EIF1AX

Located on chromosome Xp22, this gene encodes the X-linked eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1A protein (EIF1A), a crucial participant in the initiation phase of mRNA translation in ribosomes [62]. Mutations in EIF1AX demonstrate a reverse association with metastatic disease and are primarily observed in non-metastatic CM, occurring in approximately 14-20% of cases [60, 63]. In contrast, 48% of CM with D3 carry mutations in this gene, as opposed to only 3% of tumors associated with M3 [46]. Individuals with this mutation generally have an extended disease-free survival [60]. Additionally, apart from CM, mutations in this gene may also be present in ovarian and thyroid cancer, as well as leptomeningeal melanocytic neoplasms [64, 65].

Genetic investigations in this field have shown that choroidal melanocytic lesions are distinguishable from analogous skin lesions [66, 67]. Despite sharing certain genetic and biological characteristics, skin melanoma and CM undergo distinct oncogenic transformation processes [67]. However, specific skin conditions, established to be associated with an increased risk of CM development, such as blue nevus, nevus of Ota, and nevus-like melanoma, exhibit identical genetic mutations in the GNAQ/11 gene as identified in CM [49, 67, 68].

In the majority of cases, the diagnosis of CM is clinical, due to the advanced methods of multimodal imaging. However, in equivocal presentation of choroidal tumor, a choroidal biopsy may be invaluable for the diagnosis [69]. The diagnostic biopsy can be performed by different approaches: transscleral, pars plana vitrectomy (PPV) with a vitreous cutter or Essen forceps, and fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) [69-71]. Transscleral biopsy involves creating a scleral flap, followed by aspiration of tumor tissue using a fine needle, typically 25-30G, or Essen forceps [72-74]. This technique is primarily used for tumors located in the more anterior part of the globe. In contrast, a trans- retinal approach employs PPV, during which a small sample of tumor tissue is collected using either a vitreous cutter or Essen forceps [75]. Transretinal FNAB provides smaller, “cytological” samples, which may sometimes be insufficient for testing [76, 77]. Nevertheless, Shields et al. reported a satisfactory yield of 89% even in small tumors with a thickness of less than 3 mm [78]. All types of biopsies could theoretically carry a risk of extraocular seeding of the melanoma [79]. However, Bagger et al. found that the mortality related to CM was similar among biopsied and non-biopsied patients [80].

In the vast number of patients, a biopsy is not needed for the diagnosis, but the growing demand for the evaluation of prognosis for metastatic disease and overall survival is promoting the necessity of tumor evaluation even in explicit diagnosis. This is achieved with use of FNAB. FNAB allows a relatively safe insight into tumor structure and genetics, enabling a personalized approach to treatment and follow-up [70, 71, 81, 82]. For instance, FNAB of CM allows one to assess the presence of M3, which, even in small lesions with low TNM staging, clearly indicates a high-metastatic-risk tumor. The Liverpool Ocular Oncology Center promotes FNAB sampling from all treated patients for such prognostic purposes [82].

CONCLUSION

There is a visible shift towards earlier and more accurate diagnosis of CM, and clinicians are nowadays equipped with useful and easy-to-obtain tools to work with. Nonetheless, despite the advancements in diagnostic procedures, the metastatic disease is still one step ahead, as the overall survival rate has not changed significantly with time. Since the exact moment of micrometastasis seeding is still unknown, accurately distinguishing between benign CN and a transforming nevus or small CM is of great value as a first step to early diagnosis that could influence patient survival.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH