INTRODUCTION

Glaucoma is an ophthalmological disease, causing neurodegeneration of the optic nerve [1]. The global prevalence of glaucoma is estimated at 66 million, causing bilateral blindness in 6.8 million [1, 2]. In Europe there is an estimated current burden of 12.3 million individuals with glaucoma, including 6.9 million undiagnosed cases [3]. This burden is projected to grow by more than one million cases by 2050 due to changing population age structure, with a preponderance of primary open-angle glaucoma. In Poland, approximately 200,000 people suffer from glaucoma, and approximately 600,000 are at risk of developing the disease [3]. In 2020, glaucoma was responsible for 8.39% of cases of blindness [4], being considered the second most frequent cause of blindness [5]. Glaucoma can be divided into various different forms. Usually it is divided into primary congenital glaucoma (PCG), primary open angle glaucoma (POAG), primary angle closure glaucoma (PACG), and secondary glaucomas [6]. The prevalence of primary glaucoma is significantly higher than that of secondary glaucoma [7]; therefore, it is vital to understand the mechanisms behind it. In order to achieve progress in etiology, pathogenesis, and medications for primary glaucoma, understanding the genetic influence on primary glaucoma is a priority.

CYP1B1 is a gene that provides instructions for making an enzyme called cytochrome P450 1B1 [8]. CYP1B1 is involved in the metabolism of numerous substances, including xenobiotics (including drugs) and endogenous compounds such as steroid hormones and fatty acids. This enzyme is part of the cytochrome P450 family, which plays a crucial role in metabolizing various substances in the body, including drugs and hormones. The CYP1B1 genes, unlike in other cytochrome P450 family members, seems to play a significant role in eye development and is associated with various eye diseases, particularly glaucoma. Mutations in this gene are a common cause of PCG. The CYP1B1 gene is involved in the development of the anterior segment of the eye, including structures such as the trabecular meshwork (TM) and cornea. The CYP1B1 gene encodes the enzyme cyto-chrome p450 monooxygenase, and over 150 variants have been associated with a spectrum of eye diseases [8]. It also catalyzes many reactions involved in drug metabolism.

The CYP1B1 gene encodes a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily of enzymes. The cytochrome P450 proteins are monooxygenases which catalyze many reactions involved in drug metabolism and synthesis of cholesterol, steroids, and other lipids. The enzyme encoded by this gene localizes to the endoplasmic reticulum and metabolizes procarcinogens such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and 17b-estradiol. Mutations in this gene have been associated with primary congenital glaucoma; therefore, it is thought that the enzyme also metabolizes a signaling molecule involved in eye development.

The CYP1B1 gene likely plays a vital role in the pathogenesis of POAG. Research shows the influence of CYP1B1 enzyme in various ethnic groups [8–11].

The exact role of the CYP1B1 gene in the development of the eye and its association with PCG is not known. Various in silico and in vitro studies have been carried out to determine the impact of the mutations in CYP1B1 on the structure and function of the protein. The findings of these studies can help in better understanding the association of CYP1B1 with the disease pathogenesis. A study tried to correlate CYP1B1 mutations with the degree of angle dysgenesis observed histologically and disease severity in terms of age at diagnosis and difficulty in controlling IOP in six congenital glaucoma patients. The results suggested that CYP1B1 mutations could be classified based on histological findings, which may be used to correlate these mutations with disease severity [11].

The exact function of CYP1B1 protein in the eye is still unclear, but as it is a mono-oxygenase, the following roles have been proposed for its involvement in the development of the eye. CYP1B1 may participate in generation of a morphogen that plays an important role in the development of the TM and other components in the outflow system by regulating the spatial and temporal expression of genes controlling anterior chamber angle development. Hence, mutations in CYP1B1 might result in the absence of the morphogen, which in turn alters the expression of genes. Alternatively, CYP1B1 may eliminate an active morphogen and prevent its signal capacity from dispersing beyond the specific cells upon which it must act. Hence the mutations in CYP1B1 might result in the accumulation of this metabolite, producing toxic effects, which in turn may lead to developmental arrest [11].

A recent study carried out by Rojas et al. attempted to determine the pathogenic mechanisms of the disease by comparing trabeculectomy specimens of congenital glaucoma patients with normal human eyes, both at the histo-logical and ultrastructural levels. They found accumulation of amorphous material in the TM, iris insertion into the TM, bulky endothelial cells in Schlemm’s canal, and increase in the size of trabeculae. Based on these findings, it was concluded that abnormalities in the TM structure could result in the disease phenotype [12].

Most studies on this topic concern the presence of the CYP1B1 gene in glaucoma. However, this gene acts through cytochrome 450, which is a protein. However, there are fewer scientific reports on the role of this protein on glaucoma. Therefore the aim of this study was to investigate the association of CYP1B1 enzyme with PCG, POAG, and other types of glaucoma or glaucoma-reminiscent symptoms, analyze the cited literature, perform statistics in accordance with the association of mutations for various types of primary glaucoma and to find basic genetic trends in primary glaucoma, offering an expanded insight into the genetics of primary glaucoma and obtain conclusions for further studies, as well as therapy in the long term.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

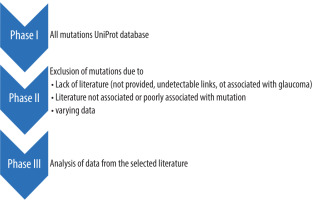

A literature search was performed in databases to identify studies on the association of cytochrome 450 protein and glaucoma in UniProt. UniProt is the world’s leading high-quality, comprehensive, freely accessible and updated base resource of protein sequence and functional information (Figure 1). We followed the mutations and checked the literature cited for each mutation, excluding some of the mutations, for various reasons; in some cases, the literature was not available. In other cases, the literature was not associated with the mutation. In some of the literature the results were too heterogeneous. After the exclusion, 39 mutations remained; they are listed in Table I [12-34]. The mutation codes in Table I were constructed using the same structure as in UniProt: a one-letter code for the wild-type amino acid at the beginning, the position of the mutation in the protein chain in the middle, and at the end the one-letter code of the amino acid introduced through mutation or one of two other types of effects – deletion (del) or nonsense mutation forming a stop codon (*). The one-letter codes for the amino acids are as follows: A – alanine, C – cysteine, D – aspartic acid, E – glutamic acid, F – phenylalanine, G – glycine, I – isoleucine, K – lysine, L – leucine, M – methionine, N – asparagine, P – proline, Q – glutamine, R – arginine, S – serine, T – threonine, V – valine, W – tryptophan, Y – tyrosine. The mutations, listed in Table I, allowed us to make a statistical analysis of the relevant mutations, in terms of determining crucial factors for genome analysis and further studies considering primary glaucoma.

Table I

Association of relevant CYP1B1 mutations with glaucoma or glaucoma-reminiscent symptoms. The association is briefly described in the second column, being the basis for further analysis

| Mutation code | Association with glaucoma or glaucoma-reminiscent symptoms | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| S28W | Found in Spanish POAG patients, one of seven mutations found in 10.8% of POAG patients | [12] |

| W57* | Found in a single patient in a case study of Peter’s anomaly | [13] |

| W57C | Mutation found in POAG, not found in healthy controls | [14, 15] |

| L59* | Found in 1 out of 236 (0.42%) patients with POAG | [16] |

| L77P | Found in 1 out of 62 Saudi families with PCG (1.61%), with a total of 57 families having at least one mutation | [17, 18] |

| M132R | Found in 1 out of 64 PCG patients (1.56%), with 24 patients with mutations in the study, one of the highest IOP (32 mmHg in both eyes) | [18] |

| Q144H | Found in Spanish POAG patients, one of seven mutations found in 10.9% of POAG patients | [19] |

| R145W | Found in Spanish POAG patients, one of seven mutations found in 10.9% of POAG patients | [19] |

| A179del | Found in 9 out of 32 (28.13%) Moroccan patients with PCG, likely associated with anterior segment dysgenesis, which causes glaucoma | [20, 21] |

| Q184S | Found in 1 in 5 (20.00%) Indian families with PCG | [22] |

| A189P | Found in 8.1% of patients with POAG and ocular hypertension, frequency higher than in controls | [12] |

| D192V | Found in 20% of Japanese patients with PCG | [23] |

| P193L | Found in 1 in 5 (20.00%) Indian families with PCG | [18, 22] |

| V198I | Probable mutation in 20% of Japanese patients with PCG | [23] |

| S215I | Found in 1 out of 12 (8.33%) Indonesian PCG patients, and 1 out of 21 (4.76%) patients in the study (Indonesian and European) | [24] |

| G232R | Found in 1 out of 31 (3.23%) French PCG patients, as well as in 4 French sisters, 2 of them with primary and 2 of them with secondary glaucoma | [16, 25] |

| F261L | Present in some PCG patients; was found in PCG newborn with paternal isodisomy of chromosome 2 | [26, 27] |

| SNF269-271del | Found in Saudi patients with PCG | [17] |

| FL276-277* | Found in a patient with elevated intraocular pressure and diffuse corneal edema | [28] |

| V320L | Probable mutation in some of the Japanese PCG patients | [23] |

| A330S | Found in 8.1% of patients with POAG and ocular hypertension, frequency higher than in controls | [12] |

| RV355del | Found in 1 in 9 (1.11%) European patients with PCG | [24] |

| V364M | Predicted as an important factor of PCG | [23, 24, 29] |

| G365W | Found in PCG families | [14] |

| D374N | Found in 7% Saudi Arabian patients with PCG | [17, 30] |

| P379L | Found in 1 in 22 PCG families from Turkey, USA, UK and Canada (in a Turkish family) | [14] |

| A388T | Found in 3 patients from Kuwait | [31] |

| R390C | Found in PCG families in India and Ecuador | [18, 32] |

| R390H | Found in 1 in 236 (0.42%) French POAG patients | [14, 16, 18] |

| R390S | Found in one French patient and one Saudi family with PCG | [17, 25] |

| I399S | Found in one French PCG patient | [25] |

| V409F | Found in Spanish patients with POAG | [12] |

| N423Y | Found in 1 in 31 (3.23%) French PCG patients and in 1 in 236 (0.42%) French patients with POAG | [16, 25] |

| G466D | Found in Indian patients with PCG | [18] |

| R469W | Found in 10-12% of Saudi Arabian PCG population | [14, 17, 30, 33] |

| E499G | Probable mutation in Japanese patients with PCG | [23] |

| S515L | Found in Indian patients with POAG, in heterozygous state | [15] |

| V518A | Both in POAG patients and in controls | [15] |

| R523T | Found in Indian patients with POAG, in homozygous state | [15] |

| D530G | Found in Indian patients with POAG | [15] |

The data from the Table I allowed us to perform the statistical analysis considering factors such as:

grouping of CYP1B1 mutations by the frequency of their occurrence;

number of CYP1B1 mutations associated with various types of glaucoma or similar symptoms, e.g. Peter’s anomaly or increased intraocular pressure (IOP);

repeatability of various amino acids, both replaced and introduced by the mutations, as well as non-substitutive effects.

RESULTS

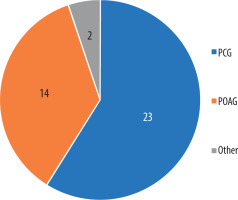

Out of 39 mutations concerning CYP1B1, 23 were found in patients with PCG, 14 of them were found in POAG, and were found in different states, i.e. Peter’s anomaly (associated with secondary glaucoma), IOP, and diffuse corneal edema (but without diagnosed glaucoma). Both papers unassociated with primary glaucoma were case studies, with only a single incident. Figure 2 presents these data.

Figure 2

Types of glaucoma or symptoms associated with relevant mutations

PCG – primary congenital glaucoma; POAG – primary open-angle glaucoma

Figure 3A shows the substituted amino acids, with the number of substitutions in the literature for each one, while Figure 3B shows the introduced amino acids by number of introductions or deletions or stop codons. The amino acids are described in both figures and Table I by their official one-letter code, while the deletion (del) and nonsense mutations forming stop codons (*) are described by their abbreviations, as in Table I. The amino acid that was most frequently substituted in the mutations was arginine (7 times), followed by valine (6 times), alanine, and serine. It is also important to note that the amino acids substituted in the papers with the most frequent occurrences (20.00% or more) were alanine, aspartic acid, glutamine, and proline.

Figure 3

A) Number of relevant mutations with a specific amino acid exchanged. B) Number of introductions of specific amino acids of other effects of relevant mutations

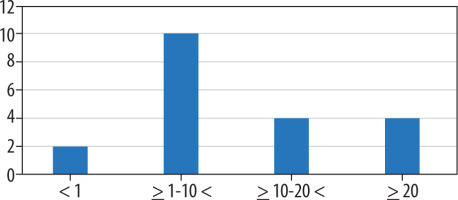

Evaluation of frequency could be made in 20 mutations. Of the remaining mutations, 3 were found in single-patient case studies, 15 mutations had no data considering their frequency or the frequency for a specific mutation could not be determined due to mutation grouping, and 1 mutation (V198I) was found as a probable but not certain mutation, despite high frequency. Figure 4 shows a very small number (2) of mutations with an occurrence lower than 1%, while mutations with higher occurrences are more frequent, especially between 1% and 10% (10 occurrences, half of relevant mutations). The lowest frequency was observed for R380H (0.42%), while the highest frequency was observed for A179 del (28.13%).

DISCUSSION

The results indicate a major role of CYP1B1 mutations in primary glaucoma, especially in PCG, but also in POAG. The frequencies of the mutations varied significantly from 0.42% to 28.13%, showing probable different relevance of various mutations. The mutations with the highest frequencies are A179 del, Q184S, D192V, and P193L. V198I also needs to be further examined, because of its high frequency, as well as the fact that it is described in the literature as a probable mutation, not a certain one. It is also vital to note the amino acids that were mostly substituted in the mutations, being arginine, valine, alanine, and serine. Both the frequent mutations and the commonly substituted amino acids should be investigated more widely, using both molecular modelling and further population and clinical studies. The molecular modelling should be focused on docking ligands, with the first examples being endogenous neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), nerve growth factor (NGF), or neurotrophin-3 (NT-3). The docking of neurotrophic factors to the CYP1B1 enzyme and observing their affinity may provide a clue for further establishing the relevance of mutations in terms of primary glaucoma. Also, the docking of popular glaucoma drugs, and exploring the process of metabolism, using molecular dynamics, can play a vital role in improving the effectiveness of glaucoma pharmacotherapy. Further clinical studies, with particular emphasis on primary glaucoma patients’ genome studies, should also be performed to provide more data for future meta analyses on the subject.

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis of the literature on the association between CYP1B1 protein (cytochrome 450 protein) and glaucoma indicates that it is a promising protein for better understanding of primary glaucoma. Further studies on the enzyme can improve both diagnosis and pharmacological treatment of PCG and POAG.

ENGLISH

ENGLISH