INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infectious disease caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. The primary modes of transmission include sexual contact with an infected person and vertical transmission. Syphilis is a chronic multisystem disease characterized by a wide spectrum of symptoms and following a cyclical course with alternating periods of exacerbation and latency. Involvement of the nervous system, including optic neuritis and other ocular manifestations, can occur at any stage of syphilis infection.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old male patient was referred to our Department due to uveitis in the right eye and optic neuritis in the left eye. The patient denied any comorbidities and chronic medication use.

Based on the physical examination and the medical records provided, it was determined that the onset of ophthalmic symptoms had occurred four months earlier. At that time, the patient was hospitalized at another ophthalmology center because of painless deterioration of vision in the right eye to the level of hand movement in front of the eye, which had persisted for two days. The patient reported no complaints in the left eye. Despite conducting examinations, the underlying cause of progressive vision loss in the right eye remained unidentified. Intravenous methylprednisolone treatment was initiated.

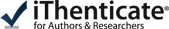

On the day of admission to our Department, the patient’s physical examination revealed loss of light perception in the right eye. The visual acuity in the left eye was 0.8. The intraocular pressure was 23 mmHg and 18 mmHg, respectively. Slit-lamp examination revealed, in the right eye, deposits on the corneal endothelium, single inflammatory cells in the anterior chamber, a non-reactive, unrounded pupil with posterior synechiae, and no fundus view. Ultrasound examination showed the presence of multiple densities in the vitreous and thickening of the choroid (Figure 1).

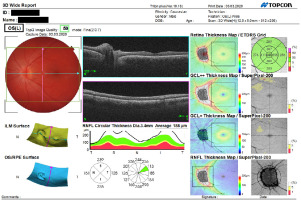

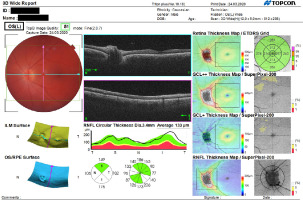

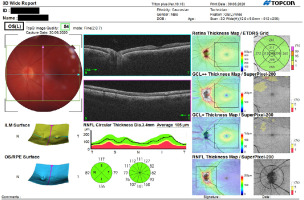

In the left eye, no pathologies were found in the anterior segment, but optic disc edema was observed (Figure 2). In addition, the patient’s optic nerve was assessed by spectral optical coherence tomography (SOCT) (Figure 3). SOCT scan of the left macula was within the normal range (Figure 4).

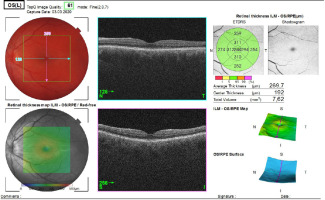

Fluorescein angiography showed multiple foci of diffuse hyperfluorescence with signs of late-phase leakage (Figure 5 A-D).

In the biochemistry panel, a number of abnormalities were found, including ESR (30 mm/h), doubtful IgM antibody test and positive IgG antibody test for Borrelia burgdorferii and HSV, and reactive WR-RPR result. Western blot assay for Lyme disease along with TPHA and FTA-ABS tests for syphilis were ordered for further verification.

The results of other laboratory tests (Quantiferon-TB, ANA, ANCA, RF, antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii, Toxocara spp., Bartonella henselae, HIV, HCV, HBV) were negative.

Contrast-enhanced MRI of the brain revealed an incidental finding – an arachnoid cyst in the right posterior cranial fossa, measuring 76 × 54 × 33 mm, deforming the right cerebellar hemisphere. Lung X-ray and abdominal ultrasound findings were normal. Neurological consultation revealed bilaterally positive Sterling’s and Rossolimo’s signs, and Babinski’s sign tendency on the left side.

During the patient’s stay in the Department, topical agents (dexamethasone drops, mydriatics) were applied to both eyes. In addition, the patient received intravenous steroid therapy (methylprednisolone at a dose of 1 g/day for a total of 5 days). A decrease in visual acuity to 0.5 was noted in the left eye.

After one week, on the day of discharge, the best-corrected visual acuity in the left eye was 0.8. The patient’s intraocular pressure was within the normal range. Physical examination revealed a raised optic disc with blurred margins (Figures 6, 7). Steroid therapy was maintained in the oral form (prednisone).

After receiving the examination results confirming the diagnosis of syphilis, oral antibiotic therapy (doxycycline 200 mg) was initiated. The patient was referred to the Neurology Outpatient Clinic to determine eligibility for lumbar puncture and potential continuation of treatment following the protocol for neurosyphilis. In addition, the patient was advised to schedule consultations at the Infectious Diseases Outpatient Clinic and the Dermatology Outpatient Clinic.

The patient remains under the care of ophthalmology and neurology specialists. The last examination, six months after hospitalization in the Ophthalmology Department, showed no sense of light in the right eye and visual acuity of the left eye at 1.0. Physical examination of the right eye revealed a clear cornea, clean anterior chamber, unrounded pupil, posterior synechiae, and pigment deposits on the lens. No abnormalities are found in the anterior segment and fundus of the left eye (Figure 8). The findings of the follow-up SOCT scan of the optic nerve were normal (Figure 9).

Discussion

The incidence of syphilis worldwide is rising, especially among high-risk populations. Those most at risk include homosexual men and HIV-positive individuals [1, 2]. Ocular manifestations are rare, found in only 1-5% of neurosyphilis cases [3]. They can occur at any stage of the disease, but are most common (4.6%) in secondary syphilis [4]. Approximately 75% of patients are male [2]. The mean age of onset of ocular symptoms is 48.6 years [5].

Syphilis can involve all ocular structures, but the most common manifestation is uveitis. Panuveitis occurs in 41% of patients with ocular syphilis, while optic nerve is involved in 22% [6]. The most common symptoms reported by patients include reduced visual acuity, ocular pain and headache, photophobia, red eyes, and increased lacrimation. In some cases, the disease may progress asymptomatically [3, 7-10]. Possible complications include the development of cataract, glaucoma, epiretinal membrane, optic nerve atrophy, or retinal detachment [8].

The first-line drug in the treatment of syphilis is crystalline penicillin at a dose of 18-24 million units/day for 10-14 days. An alternative is oral doxycycline at a dose of 200 mg twice a day for two to four weeks [1, 4].

CONCLUSIONS

Given the increased incidence of syphilis in recent years and the fact that ocular manifestations of the condition can mimic disease entities of various etiologies, it is important to include syphilis in the differential diagnostic process. In view of the broad range of symptoms, potential multiple organ involvement and associated diagnostic challenges, syphilis remains a disease requiring close collaboration of medical professionals of various specialties.

POLSKI

POLSKI