INTRODUCTION

The concept of phakomatosis was introduced into ophthalmological medical literature in 1932 by Jan von der Hoeve, who described multi-organ changes, including eye involvement, associated with neurocutaneous-ocular developmental abnormalities [1]. The onset of these disorders dates back to the fetal period, during organogenesis – the formation of organs from the individual embryonic germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm. The observed changes arise at the intersection of developmental defects, systemic diseases, and neoplastic conditions (dysplasia and/or neoplasia). Since these developmental abnormalities affect multiple organs derived from all three germ layers, phakomatoses are classified as heterogeneous disorders. They involve many different organs and constitute a group of conditions predisposing individuals to tumor development. Since van der Hoeve first published his work on phakomatoses, over 60 new disease entities associated with phakomatosis have been described [2]. This makes these developmental abnormalities a consistently significant concern, impacting both children and adults. The classic descriptions of the disease by von der Hoeve remain a reference point for contemporary researchers and clinicians across various specialties.

Within the group of phakomatoses, four major disease syndromes are distinguished: Sturge-Weber syndrome (angiomatosis encephalotrigeminalis), neurofibromatosis type 1 (peripheral form) – Recklinghausen disease, and neurofibromatosis type 2 (central form), tuberous sclerosis (Bourneville disease, epiloia), and von Hippel-Lindau disease, characterized by capillary malformations of the retina and cerebellum [3–6]. They are associated with the presence of tumors of the hamartoma type. Hamartomas are composed of mature tissues normally found in the affected organ, but arranged in a disorganized, chaotic manner within the tumor and often present in excess. The distinct neuro-ophthalmological features of each of these disorders play a crucial role in clinical diagnosis. The above-mentioned pathological changes have a genetic basis [7, 8].

STURGE-WEBER SYNDROME

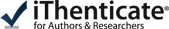

Sturge-Weber syndrome is a developmental disorder that does not show hereditary predisposition [7]. Recent studies indicate that Sturge-Weber syndrome results from sporadic genetic mutations in the GNAQ gene located on the long arm of chromosome 9 [4]. It is characterized by vascular malformations of the face in the form of port-wine stains distributed along the branches of the trigeminal nerve (Figure 1), as well as vascular malformations of the leptomeninges and the brain, in addition to characteristic changes involving the visual system. In most cases, cerebral and ocular lesions are located on the same side as the facial port-wine stain. The underlying cause of the brain abnormalities is a disturbance in the development of the fetal vascular system, triggered by the persistence of primitive vascular plexuses surrounding the cephalic portion of the neural tube, which are responsible for the development of the parietal and occipital brain structures [7]. Among the ocular changes observed, vascular malformations of the eyeball can be distinguished. These may affect the episclera and sclera (40%) (Figure 2), as well as the iris, ciliary body, and choroid (Figure 3). The abnormalities may also lead to the development of glaucoma, which is present in about 30% of children. In Sturge-Weber syndrome, glaucoma occurs in 60% of cases during infancy, while in 40% it manifests later in childhood or beyond. The etiopathogenetic factors leading to glaucoma in this syndrome result from increased pressure in the episcleral veins due to vascular malformations, hyperemia of the ciliary body with hypersecretion, or structural abnormalities within the anterior chamber.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE 1: PERIPHERAL

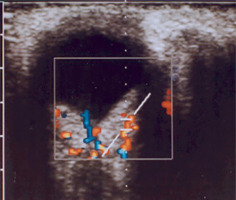

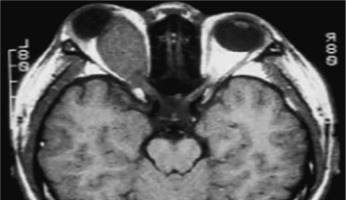

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) is a phakomatosis caused by a mutation in the NF1 gene located on chromosome 17q11.2. This gene encodes the protein neurofibromin, which is responsible for regulating cell division and proliferation [5, 6]. The traditional designation of these abnormalities as von Recklinghausen disease is now considered largely historical. The disease has an estimated prevalence of approximately 1 : 3,500 live births and affects 1 : 4,000 to 1 : 5,000 individuals in the general population [4, 8, 9]. Neurofibromatosis type 1 is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner, although more than half of cases occur sporadically, representing new mutations [9]. In most children, the new mutation is inherited from a parent. The risk that a child of an affected parent will develop neurofibromatosis type 1 is approximately 50%. A characteristic feature of the disease is the appearance of pigmented patches on the skin, referred to as café-au-lait spots. The presence of at least five to six such spots, covering any region of the child’s body, is indicative of the disease. Freckles and areas of hyperpigmentation are also observed in regions with limited light exposure, such as the axillae, groin, and beneath the breasts in women (Crowe’s sign). Also, diffuse neurofibromas occur in the skin, brain, and spinal cord. The primary distinguishing feature of changes in the eyeball is the presence of Lisch nodules on the iris and other characteristic ocular features of this syndrome [10–12]. Lisch nodules arise as a result of developmental disturbances and uncontrolled divisions of mast cells and pigment epithelium forming the outer surface of the iris [8, 10, 11] (Figure 4). They are a consequence of damage to the choroidal melanocytes and, histologically, correspond to melanocytic hamartomas of the iris. A diagnosis is warranted by the presence of at least two Lisch nodules. The role of solar radiation in their development remains controversial [12]. Lisch nodules are visible on slit-lamp examination as small, vascularized, elevated structures of the iris, measuring 0.1 mm to 2 mm in size, in various shades of brown. Their position within the iris crypts can occasionally make them difficult to detect. Lisch nodules occur in 10% to 90% of children with this syndrome, and their number increases with age. The nodules do not affect visual acuity, but when they are numerous and asymmetrically distributed between the eyes, they may lead to cosmetic concerns. Glaucoma in neurofibromatosis type 1 coexists in approximately 50% of cases with neurofibromas of the upper eyelid and hemifacial atrophy. Congenital glaucoma results from developmental defects in the anterior chamber angle during embryogenesis. Glaucoma can also be secondary to angle closure caused by phakomata of the iris and ciliary body. Fibrovascular proliferations imply the development of neovascular glaucoma. Optic nerve glioma occurs in 15% of children with neurofibromatosis type 1. The disease may also be associated with other central nervous system tumors, such as neurofibromas or meningiomas. Optic nerve glioma is typically unilateral and presents in approximately 70% of cases before the age of 10. It occurs more frequently in females, with an incidence ranging from 25% to 50% (Figure 5). The symptoms of glioma progress slowly. The initial manifestation is typically painless and gradually progressive proptosis. Due to its slow onset, this change may go unnoticed by those in close daily contact with the child – such as parents or caregivers. Quite often, it is an outsider – someone who has not seen the child for an extended period – who first notices the proptosis. As the glioma advances, additional symptoms such as visual disturbances, reduced visual acuity (potentially leading to complete blindness), and strabismus begin to emerge, eventually drawing the attention of those closest to the child to the deterioration of their visual system. The growth of the tumor is accompanied by swelling of the optic disc, followed by its atrophy. Pulsatile exophthalmos, which may arise as a consequence of conditions associated with neurofibromatosis type 1, often has a silent, asymptomatic course, without orbital bruits, due to a defect in the greater wing of the sphenoid bone and herniation of brain tissue into the sphenoid sinus and orbit. Other pathological changes that occur during the development of optic nerve glioma include plexiform neurofibroma of the eyelids with associated ptosis and dysplasia of the orbital bone, leading to compression of the optic nerve. Pigmented uveal nevi, increased incidence of choroidal melanoma, and retinal glial hamartomas are observed. Refractive errors can occur in both neurofibromatosis type 1 and type 2 [13]. Other rare ocular manifestations include prominent cor-neal nerves, congenital eversion of the iris pigment epithelium, iris nevi or hamartomas, and generalized choroidal thickening.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS TYPE 2: CENTRAL

The cause of the disease is a mutation in the NF2 gene located on the long arm of chromosome 22 (locus q 12.2), which encodes the protein merlin (also known as schwannomin or neurofibromin 2) [14–16]. This protein is involved both in the regulation of the cell cycle as a tumor suppressor and in the formation of cytoskeletal structures [11]. The disorder is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. Two tumor suppressor genes implicated in this abnormality have been identified: TSC1 on chromosome 9 and TSC2 on chromosome 16. The clinical manifestations are associated with the presence of these genes, and may be affected by mutations in one of them, namely the 9q gene (TSC1) or the 16p13 gene (TSC2). Sporadic mutations account for 70% of cases, while familial cases represent 30%. It is now known, however, that only 29% of patients present with the full clinical picture of the disease, whereas in 6% of children no features of the disorder can be detected [10, 11, 14–16]. While most cases arise sporadically and without a known family history, approximately one-third of patients inherit a pathogenic variant of either the TSC1 or TSC2 gene. Due to its autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, males and females are equally likely to transmit the condition to their children. The condition typically manifests in early childhood, around the age of 2. The most characteristic symptoms of neurofibromatosis type 2 include bilaterally located auditory nerve tumors, intracranial tumors, and café-au-lait skin spots, which are present in smaller numbers than in neurofibromatosis type 1. Ocular manifestations include lens opacities of varying severity, such as juvenile posterior subcapsular and capsular cataracts, and peripheral cortical cataracts. Lisch nodules are also present, though less numerous than in phakomatosis type 1; iris hamartomas have been described, and retinal hamartomas may occur. Refractive errors are also observed.

TUBEROUS SCLEROSIS

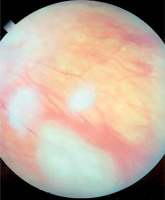

Symptoms of tuberous sclerosis (Bourneville disease, epiloia) involve multi-organ abnormalities of ectodermal and mesenchymal origin, causing abnormalities in the skin, brain tissues, central nervous system, kidneys, heart, lungs, and the organ of vision [14–16]. Skin changes may result from depigmentation, leading to lightening of the skin in areas affected by pigment loss. Facial skin redness may result from neurofibromas with a prominent vascular component. Additionally, raised patches resembling an orange peel texture (shagreen skin) are often observed, particularly on the dorsal region. Cerebral manifestations include autism spectrum disorders and epileptic seizures. Neurological complications are the leading cause of morbidity, whereas renal disease represents the primary cause of mortality. Another possible manifestation is lymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM), a lung disease that occurs more frequently in women. Delayed psychomotor development and intellectual disability are observed in affected children. Other abnormalities may include dental enamel defects, rubbery lesions of the tongue and adjacent areas, as well as rough periungual growths. The characteristic triad of symptoms, also known as Vogt’s triad, is a key diagnostic feature of the disease. Symptoms include intellectual disability, epilepsy, and sebaceous adenomas (Pringle’s syndrome), which requires differentiation from rosacea. Ocular abnormalities rarely cause significant visual impairment and are usually asymptomatic. Hemangiomas and fibromas are observed on the eyelids. Glial hamartomas of the retina and optic disc (astrocytic hamartomas) occur in two clinical forms (Figures 6 and 7). The first group comprises phakomata presenting as nodules with a smooth surface, flat in shape; in young children, the nodules are gray-white and have indistinct borders. The second group includes nodules with an irregular surface, elevated profile, well-defined margins, and an opaque, shiny, yellowish-white appearance, often containing calcifications and resembling mulberry fruit (other descriptive terms include “tapioca-like clusters” or “fish-scale” appearance). Other observed abnormalities include colorless spots on the iris, optic disc edema, areas of retinal depigmentation, hypopigmentation of the fundus, and brain tissue defects (colobomas) as a complication of hydrocephalus. The presence of intraocular pathologies requires differentiation from retinoblastoma. Other ocular changes observed in patients with Bourneville’s disease include refractive errors, such as myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, as well as strabismus.

VON HIPPEL–LINDAU DISEASE

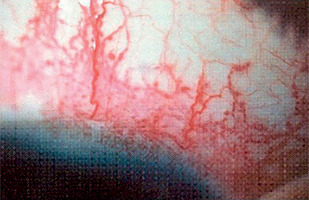

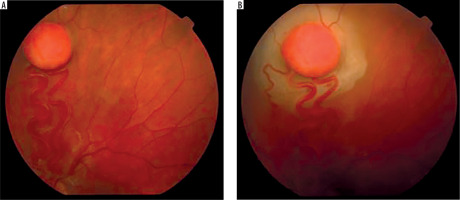

It is a very rare disease, affecting an estimated one in 30,000–40,000 individuals, with around 1,000 cases reported in Poland. The condition is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. The syndrome is caused by constitutional mutations of the VHL tumor suppressor gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3. Constitutional mutations affecting a single gene are present in all cells of the body and represent the primary cause of pathology in this type of genetic disorder. The syndrome is characterized by the presence of hemangioblastoma-type tumors in the cerebellum, spinal cord, brain, visceral organs, and the eye [16]. The tumors consist of components of hemangioblastomas [6]. Visceral abnormalities are associated with the presence of pancreatic and renal cysts, as well as polycythemia. Tumors such as pheochromocytoma and adenocarcinoma may also occur. Hemangioblastomas that develop in the brain and spinal cord can cause headaches, vomiting, weakness, and loss of muscle coordination (ataxia). Within the ocular globe, capillary malformations affecting the optic nerve and retina are detected. The malformations appear as tumors in both eyes, located peripherally and centrally [6] (Figure 8A, B). Peripheral distribution is characterized by the presence of tortuous, dilated vessels that supply and drain blood from the tumor. In contrast, centrally located vascular tumors typically exhibit an endophytic growth pattern and lack afferent and efferent vessels associated with vascular malformations. Disease progression may lead to retinitis and retinal detachment, iridocyclitis, and rubeosis iridis. The changes may result in the development of secondary glaucoma.

Figure 8A, B

Retinal vascular malformation in von Hippel-Lindau syndrome – before treatment and during therapy

The diagnosis of phakomatosis is based on a thorough medical history, which includes the presence of phakomatosis-type lesions or other systemic disorders in the family, as well as symptoms reported by the child or their parents. Ophthalmologic examination includes all elements of the clinical assessment, performed under local or general anesthesia, depending on the child’s age. Important diagnostic tests include genetic analyses [17]. Prenatal diagnosis is possible through molecular testing of amniotic or chorionic cells. Genetic counselling plays a crucial role in supporting informed reproductive decision-making for patients and at-risk family members [18, 19]. Imaging examinations are also important in the diagnostic work-up. These include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT) of organs and systems potentially affected by the disease process – such as the head and brain – as well as ocular and orbital ultrasound, chest X-ray, electrocardiography (ECG), electroencephalography (EEG), and other examinations required for an accurate diagnosis. An essential part of diagnosis and therapy involves consultations from other medical specialties and interdisciplinary collaboration.

There is no causal treatment for phakomatosis. Management strategies are tailored to the individual clinical profile of each patient, ensuring a personalized approach. If indicated, symptomatic therapy is introduced. When a refractive error is present, corrective lenses are prescribed to enhance visual acuity. Pharmacological therapy may be administered, and in selected cases, surgical intervention is considered. Glaucoma is managed with conservative or surgical treatment, depending on the patient’s local ocular condition and overall health status. Epilepsy is treated with antiepileptic drugs or, when indicated, surgical intervention. Surgical treatment within the eye includes laser therapy and cryotherapy for vascular lesions affecting the eyelids, eyeball, and retina; procedures for retinal detachment repair; pars plana vitrectomy; photo-dynamic therapy; intravitreal administration of anti-VEGF agents; as well as cataract and strabismus surgeries. Regular ophthalmologic monitoring of children with phakomatosis is essential, since disease manifestations may emerge at a later stage and existing lesions may progress with advancing age. Due to the presence of additional health issues and cognitive impairment in some children, these patients receive individualized education or attend specialized educational and care centers equipped to support individuals with neurocutaneous syndromes (phakomatoses). Children diagnosed with phakomatosis require close and effective collaboration between healthcare providers and the child’s parents, along with consistent medical follow-up that includes regular ophthalmologic evaluations. Adults with features of phakomatosis should also undergo regular follow-up examinations and adhere to the recommendations of their attending physician.

POLSKI

POLSKI