INTRODUCTION

The autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus and spondyloarthropathy are becoming increasingly frequent. They are managed by different immunosuppressive agents including steroids and methotrexate (MTX). Steroids have anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive action with a decrease of CD4 lymphocytes and monocytes. Methotrexate is immunosuppressive drug with potent effects on cellular and humoral immunity with decrease of production of immunoglobulins. It also inhibits pro-inflammatory cytokine production [1]. Therefore, its simultaneous administration can lead to reactivation of opportunistic infections such as herpes, cytomegalovirus and toxoplasma. Toxoplasma gondii infects more than 30% of the population during their life (sero-positive IgG), but only a small minority of people infected will develop retinitis. Many cases of retinitis can be asymptomatic if the macula is not involved. Additionally, the protozoan survives as latent bradyzoite (cyst) in human cells, mostly in muscles and the central nervous system, and in a situation of impaired immunity, the cysts may be a source of recurrences.

CASE REPORT

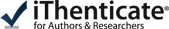

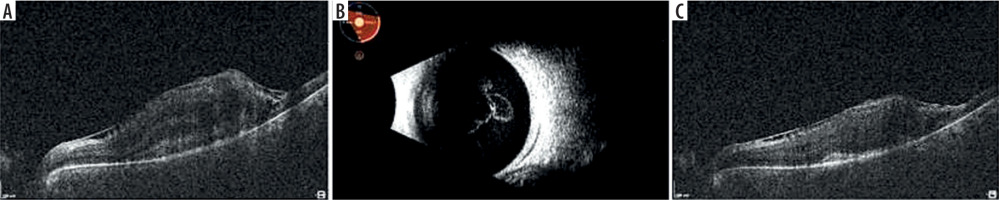

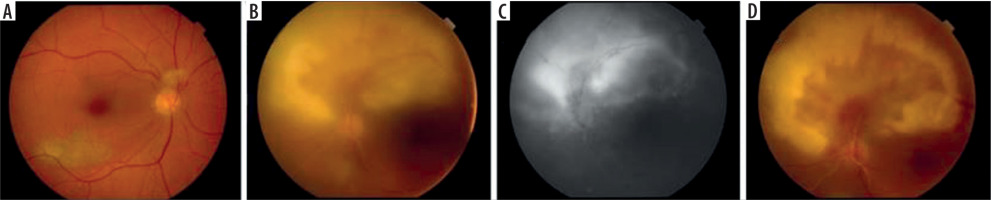

A 54-year-old woman was hospitalized due to necrotic retinitis of her left eye (LE). She noticed floaters and decrease of visual acuity (VA) one month earlier with concomitant general weakness. As she experienced the similar floaters in her right eye (RE) about one year earlier with its spontaneous resolution, she did not initially seek medical attention. Her medical history was notable for peripheral spondyloarthropathy (HLA-B27+) for 10 years. The disease had been controlled by oral MTX 25 mg once weekly for 3 years, methylprednisolone 3 mg daily for 10 years, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). She also suffered from post-steroidal diabetes and osteoporosis. At admission her VA (Snellen) was 1.0 and 0.4 for RE and LE, respectively. Right eye showed atrophic perifoveal scar (Figure 1A) and LE mild anterior segment inflammation. Fundus eye examination found vitreous inflammatory opacities and large nonhomogeneous inflammatory lesion with signs of diffuse arteritis (Figure 1B). Fluorescein angiography (FA) showed the hypofluorescence area with hyperfluorescent center (Figure 1C). Serology testing was notable for toxoplasma (IgG > 200, positive if > 3.0, and IgM 0,48, negative if < 0.5), cytomegalovirus (CMV; IgG 177, positive if > 6.0, IgM not reactive) and herpes zoster virus (HZV; IgG 448.47, positive if > 110, IgM negative). Syphilis, HIV, and herpes virus type 1 and 2 were negative. Blood count revealed slightly decreased levels of monocytes and lymphocytes. Methotrexate treatment was discontinued due to immunosuppression. Oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TS) twice a day and clindamycin 1 mg intravitreally twice with an interval of 5 days were given. Additionally, oral acyclovir 800 mg 5 times per day was prescribed. In the following 10 days of hospitalization, the inflammation decreased and VA increased to 0.5 (Figure 1D). Patient was discharged from the hospital on methylpredniso-lone and TS. At the 3-week follow-up, massive retinal neovascularization was found with persistent retinal inflammation (Figure 2A–C). Two complementary intravitreal injections of clindamycin resulted in rapid improvement. The signs of arteritis almost disappeared, and panretinal photocoagulation was urgently done. Prophylactic doses of TS (1 tablet every 3 days) were prescribed. On follow-up, VA was gradually decreasing to 0.02 due to progressive macular edema and membrane (Figure 3A). At the 8-month follow-up visit spontaneous posterior vitreous detachment (PVD) with concomitant vitreous hemorrhage occurred and VA was hand movements (Figure 3B). Anti-VEGFs (aflibercept twice and faricimab once) were injected in case of macular edema aggravation. At the 18-month follow-up visit VA was 0.1 (Figure 3C).

Figure 1

A) Fundus photography one year before the event with atrophic scar in the macula of RE and Weiss ring just above optic disc. B) Fundus photography at presentation with arcuate snow-white, fluffy lesion and diffuse arteritis. C) Fluorescein angiography of late phase shows intensive hyperfluorescence in the center and large mild hyperfluorescence around, reinforced at the borders. D) Less inflamed lesion 10 days later before discharge

Figure 2

A) Fundus photography 3 weeks after discharge with macular infiltrate typical for toxoplasmosis with less pronounced arteritis. B) Fluorescence angiography of early phase with hypofluorescent macular focal lesion and massive hyperfluorescent retinal neovascularization. C) Leakage from the new vessels, hypofluorescent arcuate active lesion between atrophic retina and neovascularization and no perfusion of vessels in the superior hemisphere

DISCUSSION

Cases of opportunistic eye infections are a well-described phenomenon in HIV patients and transplant patients, however not in patients with autoimmune diseases [2]. The reported patient was immunosuppressed due to long methylpredniso-lone and MTX use. The initial examination showed the diffuse necrotic retinitis with Kyrieleis arteritis. Such presentation is atypical for retinal toxoplasmosis but possible during immuno-suppression [3]. Balansard et al. reported that 2/3 of necrotizing retinopathies simulating acute retinal necrosis had toxoplasma as origin [4]. Polymerase chain reaction tests were unavailable for anterior chamber/vitreous examination, neither the coefficient of Goldmann-Witmer was measured. Therefore initial differential diagnosis included opportunistic infections in relation to positive IgG results: CMV, HZV and toxoplasmosis. Cytomegalovirus retinitis usually occurs in advanced HIV patients with low CD4+ lymphocyte counts, however it was also reported in patients taking immunosuppressive treatment. It can have different clinical images and it responds to ganciclovir/foscarnet/cidofovir treatment. No such treatment was given to our patient. In addition occlusive vasculitis seems to be panretinal in patients with limited immune dysfunction [5-8]. Progressive outer retinal necrosis (PORN) was also an unusual diagnosis because it occurs in patients with very low CD4+ lymphocyte counts, and it is difficult to manage even with intravenous/intravitreal gan ciclovir/foscarnet. It progresses fast, and it results in severe loss of vision. Importantly, there is no associated vasculitis [9]. Acute retinal necrosis usually occurs in immunocompetent patients and it starts at the periphery [10]. To stop its rapid progression, intravenous acyclovir is used. At the beginning oral acyclovir was prescribed in our patient while awaiting serology results. According to her history, our patient also experienced the first episode of retinitis in her RE one year before. This episode was relatively mild without affecting visual acuity and it healed itself. Such a self-healed retinitis is typical for toxoplasmosis in immunocompetent patients [11]. The second inflammation which affected the contralateral eye, was much more severe, apparently due to the longer duration of immunosuppressive treatment. Retinitis was centrifugally ongoing with scarring in its center. The process stopped after treatment against toxoplasmosis despite ongoing methylprednisolone use [12]. Retinitis of our patient was also complicated by 2 types of arteritis. The first was Kyrieleis arteritis, which involves accumulation of periarterial exudate. It can occur due to various infectious etiologies, but the most common pathogen seems to be toxoplasmosis [13]. This periarteritis resolved with treatment. The second type of vasculitis was occlusive and it spread by contiguity with active inflammatory lesions. This vasculitis occluded all vessels covering superior hemisphere and resulted in the large zones of ischemia and retinal neovascularization with proliferative vitreoretinopathy development despite prior panretinal photocoagulation [14]. Persistent neovascularization and large post-inflammatory scar were likely to contribute to macular edema. Anti-VEGF use was postponed due to no PVD and significant vitreoretinal tractions on atrophic retina with hypothetic retinal detachment [15, 16]. As spontaneous and complete PVD occurred , anti-VEGF injections were performed. Macular edema decreased however, it subsequently recurred [17].

POLSKI

POLSKI